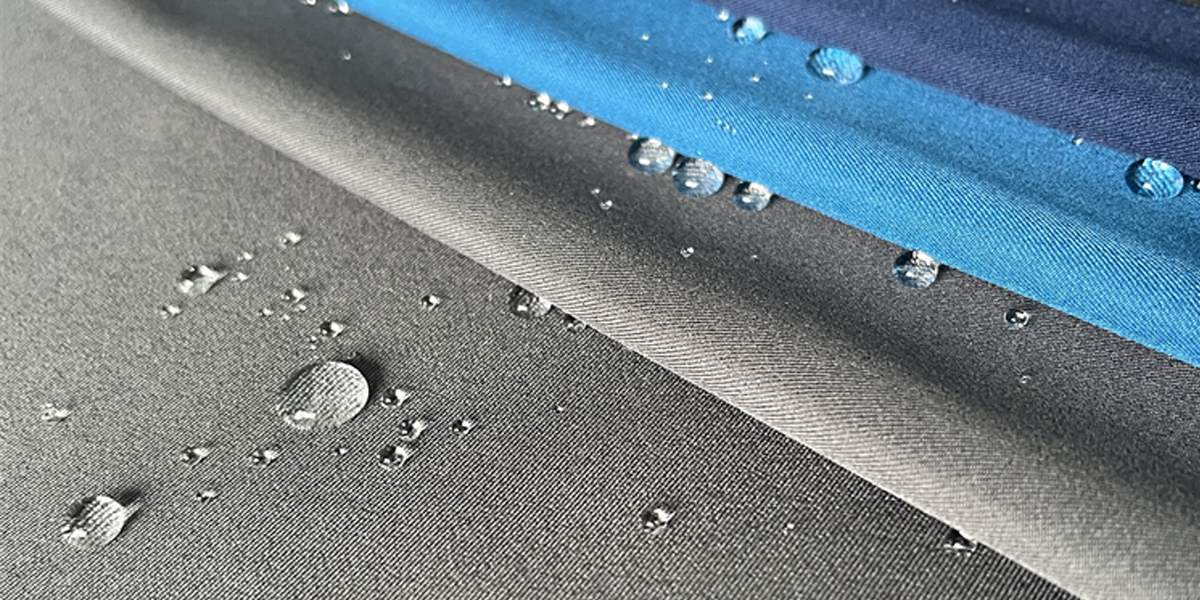

Modern woven workwear fabric achieves its water-repellent finish via specialized chemical treatments. These alter surface tension, causing water to bead and roll off. This creates a water resistant textile, vital for items like polyester spandex fabric for medical scrub, TSP fabric for medical wear, and TSP hospital uniform fabric, often as TSP easy care fabric. This market was $2572.84 million in 2023.

Key Takeaways

- Special coatings make workwear fabrics repel water. These coatings change the fabric’s surface. Water then beads up and rolls off, keeping you dry.

- Old water-repellent chemicals, called PFCs, harm the environment and health. New, safer options now protect fabrics without these risks.

- You can make your water-repellent clothes last longer. Clean them properly and use heat to refresh the coating. This helps the fabric keep water out.

The Science of Water Repellency in Workwear

Understanding DWR (Durable Water Repellent)

When I look at modern workwear, I see a lot of innovation, especially in how fabrics handle water. The secret often lies in something called Durable Water Repellent, or DWR. DWR is a special coating manufacturers apply to fabrics. This coating makes the fabric water-resistant, or hydrophobic. Historically, most DWR treatments used fluoropolymers. These coatings are usually very thin. Manufacturers apply them by spraying or dipping the fabric in a chemical solution. They can also use chemical vapor deposition (CVD). CVD is great because it uses fewer harmful solvents and less DWR material. It also creates a super-thin waterproof layer that does not change how the fabric looks or feels much.

DWR works by lowering the surface free energy of the material. This means the fabric’s surface energy becomes lower than the surface tension of water. When water hits the fabric, it forms beads and rolls off. This prevents water from soaking in, which keeps you comfortable and dry. Water repellency in textiles depends on how much a liquid sticks to a solid surface. Less sticking means more repellency. A fabric’s ability to resist water depends on several things: the chemical makeup of its surface, how rough it is, how porous it is, and what other molecules are on it. Tightly woven fabrics also help. Adding fine microparticles can reduce pore channels, which further blocks fluids.

Water repellency is all about changing surface tension. Water molecules prefer to stick to each other rather than to a treated fabric. We achieve this by applying special chemicals. These chemicals form a hydrophobic layer on the textile. This layer stops water droplets from getting in. Instead, the droplets bead up and roll away. These finishing agents work in a couple of ways. First, chemicals like fluorocarbons or silicones reduce the surface energy of the fibers. This makes it hard for water to spread. Second, advanced agents create rough, textured surfaces at a tiny level. This reduces the contact area between water droplets and the fabric, making the water bead up even more.

The hydrophobic effect uses surface tension. Water-resistant coatings and tightly woven fibers are non-polar. This means water molecules cannot form bonds with them. So, water droplets stay on the surface, held together by their own forces. When a droplet gets too heavy, gravity pulls it off. These hydrophobic chemical coatings go on through spray-on or dip treatments. Fabrics soak in solutions with water-repelling chemicals, then they dry. As they dry, these chemicals, like silicone, wax, or certain fluorocarbons, bond to the individual fibers. This changes the surface tension of the fibers. It makes it hard for water and other liquids to get into or stick to the fabric.

Chemistry of Hydrophobicity: PFCs and Alternatives

For a long time, the go-to chemicals for DWR were per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFCs. Specifically, long-chain C8 fluorocarbons were the standard. These chemicals were very effective at repelling both water and oil. They also had high chemical and thermal stability. However, we learned about the environmental and health concerns linked to these substances. After C8 fluorocarbons were banned, shorter-chain C6 treatments became a temporary solution.

We now know that fluorotelomers, which are part of PFCs, break down into dangerous PFC acids. This adds to PFC pollution. Studies on trout show this breakdown can happen through digestion. This raises concerns about food contamination and direct absorption in humans. The fluorocarbon industry once claimed slow breakdown in soil. However, EPA research showed a much faster rate. They concluded that fluorotelomer-polymer breakdown is a big source of PFOA and other fluorinated compounds in the environment. C6-based fluorotelomers also break down into PFC acids, like PFHxA. While PFHxA might be less dangerous than PFOA, it is still a concern. Other fluorotelomer acids from this breakdown have shown toxicity to aquatic life.

PFCs are a problem because many break down very slowly. They can build up in people, animals, and the environment over time. Research suggests that exposure to certain PFCs can lead to bad health outcomes. For example, PFC exposure may delay puberty in girls. This could lead to higher risks of breast cancer, kidney disease, and thyroid disease later in life. It has also been linked to lower bone mineral density in teens, which can cause osteoporosis. Studies show a link between PFC exposure and an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes in women. Some PFCs may also increase the risk of thyroid cancer. Large studies on humans and animals show liver damage from PFC exposure. PFCs build up in body tissues like the liver, possibly contributing to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Because of these concerns, I see a big push for PFC-free alternatives. Many companies now offer great options. For example, Rockgeist offers PFC-free fabrics like XPac’s Cotton Duck series and EcoPak’s offerings. Shell-Tech Free M325-SC1 and Shell-Tech Free 6053 are water-based finishes that use hydrophobic-reactive polymers. They provide high water repellency and last through many washes. Altopel F3® is another good option for cotton and synthetic fibers. Schoeller Textil AG has developed Ecorepel®, a PFC-free DWR finish that mimics how plants naturally protect themselves. It forms a thin film around fibers to repel water and dirt.

Other notable PFC-free solutions include zeroF products and ECOPERL by CHT, BIONIC-FINISH® ECO by Rudolf Group, and Ecoguard-SYN (Conc) by Sarex. Sciessent offers Curb Water Repellent products, which are 100% fluorine-free and biodegradable. Teflon EcoElite provides non-fluorinated stain repellent technology. Daikin has Unidyne XF for PFC-free water repellency. DownTek offers PFC-free water repellent down. NEI’s Nanomyte SR-200EC and NICCA’s Neoseed Series are also PFC-free. Polartec eliminated PFAS in DWR treatments across its fabrics. Sympatex laminates have always been PFAS and PTFE free. OrganoClick’s products are PFAS-free and biodegradable. Even Snickers Workwear offers wash-in textile waterproofing free from fluorocarbons.

One impressive alternative is Empel™. It shows superior water repellency, absorbing only one-third the water compared to leading C0 and C6 finishes. It is PFAS-free and non-toxic, with Oeko-Tex® certification. Empel uses a water-free application process, which reduces pollution and energy use. It offers long-lasting durability because it forms a molecular bond with fibers. Plus, it keeps the fabric soft and breathable, which is crucial for comfortable woven workwear fabric.

Applying Water-Repellent Finishes to Woven Workwear Fabric

Industrial Application Processes

I find the industrial application of water-repellent finishes fascinating. Manufacturers primarily use a method called pad-dry-cure. First, they soak the woven workwear fabric in a solution. This solution contains DWR agents, binders, softeners, and catalysts. Next, rollers squeeze the fabric to achieve a desired wet pick-up. Then, they dry the product. Finally, they cure it at specific temperatures and durations. This curing step is crucial. It activates the treatment. For example, drying happens between 100°C and 120°C. Curing then takes place at 150°C to 180°C. I also know many DWR treatments are heat-activated. A quick spin in a dryer on low or medium heat can help rejuvenate the finish. This resets the treatment on the fabric’s surface. It often restores water beading without needing a full re-treatment. If water repellency starts to diminish, I consider reactivating the DWR using a low heat setting in the dryer, if the care label permits. For Gore-Tex items, I might even use a steam iron on a warm setting, placing a towel between the iron and the garment.

Fabric Structure and Weave for Repellency

Beyond chemical treatments, the fabric’s physical structure also helps with water repellency. I see that the way manufacturers weave the fabric makes a big difference. Tightly woven fabrics naturally resist water better than loose weaves. The close interlace of threads creates a denser barrier. This makes it harder for water droplets to penetrate. Think of a very fine, dense woven workwear fabric. Water struggles to find gaps to pass through. This physical resistance works together with the chemical DWR finish. It creates a more effective and durable water-repellent garment. A plain weave, for instance, with its simple over-under pattern, can be very dense. This density reduces the size of the pores in the fabric. Smaller pores mean less space for water to get through. This combination of a tight weave and a good DWR treatment gives us the best protection.

Performance, Durability, and Maintenance

Measuring Water Repellency Effectiveness

I often wonder how manufacturers determine if a water-repellent finish truly works. They use several key performance indicators and tests. These tests help us understand how well a fabric resists water.

One common test is the Hydrostatic Head Test (AATCC 127). I see this test measures how much water pressure a fabric can withstand before water penetrates it. They place the fabric under a column of water. The height of the water column, measured in millimeters (mm H₂O), indicates the fabric’s resistance. For example, I know apparel with more than 1000 mm is considered waterproof. For extreme conditions, like tents or military gear, they require over 3000 mm. The AATCC 127 test uses an electronically controlled pump. It applies hydrostatic pressure to the fabric’s underside. An observation light helps detect water droplets. This test is common for outdoor sports clothing and medical protective materials.

Another important test is the Spray Rating Test (ISO 4920:2012 or AATCC 22). I find this test evaluates a fabric’s resistance to surface wetting. They spray water onto a taut fabric specimen under controlled conditions. Then, they visually rate the wetted pattern. The rating scale goes from 0 (fully wet) to 100 (no sticking drops). International buyers often require more than 90 grades for outdoor jackets. This test helps assess the water resistance of various fabric finishes. The results depend on the fibers, yarn, fabric construction, and finish.

Other tests also contribute to a full picture of fabric performance:

- Drop test: This checks how water beads and rolls off the surface.

- Absorbency test (Spot test): I use this to see how much water the fabric absorbs.

- AATCC 42: This measures water penetration in grams. For example, medical gowns might need less than 1.0 g/m.

- Bundesmann test (DIN 53888): This determines both water absorption percentage and abrasion resistance. It is suitable for workwear and heavy-duty textiles.

Beyond water repellency, I also consider other fabric properties for overall performance:

- GSM (Grams per Square Meter): This tells me the fabric’s weight.

- Bursting strength: I check this for resistance to tearing.

- Tensile strength: This measures how much force the fabric can withstand before breaking.

- Abrasion resistance (ASTM D4966, Martindale abrasion tester): This shows how well the fabric resists wear from rubbing.

- Air permeability: I look at this for breathability.

- Color fastness to wash (ISO 105 C03): This ensures colors do not fade after washing.

- Color fastness to water (ISO 105 E01): This checks color stability when wet.

- Color fastness to perspiration (ISO 105-E04): I use this to see if sweat affects the color.

- Rubbing fastness (ISO-105-X 12): This measures how much color transfers when rubbed.

For workwear, I often refer to the EN 343 Standard (UK). This standard assesses the entire garment. It considers the water resistance of the fabric and seams, garment construction, performance, and breathability. It categorizes garments into four classes (Class 1 to Class 4) for both water resistance and breathability. Class 4:4 offers the highest protection. I find this standard very helpful for choosing reliable water-repellent woven workwear fabric.

Factors Affecting Finish Durability

I have learned that even the best water-repellent finishes do not last forever. Several factors affect their durability. Understanding these helps me maintain my workwear better.

One major issue is contamination. DWR finishes, including waxes and silicones, are easily contaminated by dirt and oil. This contamination causes these finishes to rapidly lose their effectiveness. When the DWR degrades, the fabric surface becomes soggy. This creates a clammy, wet feeling next to the skin, even if water does not penetrate the garment. This loss of effectiveness reduces the garment’s functional lifetime.

Abrasion also plays a significant role. Natural abrasions and repeated use cause wear-and-tear on waterproof garments. This wear-and-tear leads to areas where the DWR finish wears off over time. Excessive abrasion from sources like rocks, repeated contact with hipbelts and shoulder straps, or numerous launderings diminishes DWR performance. When this happens, reapplication of DWR becomes necessary.

Improper laundry practices can severely damage DWR finishes. I have found that ordinary laundry detergents destroy DWR properties. They deposit chemical residue. This residue, which can accumulate to 2% of the fabric’s weight, consists of perfume, UV brightening dyes, salts, surfactants, processing aids, washing machine lubricants, oils, fats, and polymers. This residue stiffens the fabric, binds fibers, and covers the fluoropolymer in the DWR. It prevents water from beading up and causes it to soak into the fabric. Fabric softeners further worsen this issue by adding more residue.

I always recommend using pH-neutral detergents designed for technical outerwear. These are often water-based, biodegradable, and free of dyes, whiteners, brighteners, or fragrance. Detergents suitable for sensitive skin are often safe for gear. I avoid conventional detergents, bleach, fabric softener, and dry cleaning. These can clog pores, damage DWR coatings, and reduce waterproof/breathability ratings.

To extend the lifespan of water-repellent workwear, I follow specific maintenance practices:

- Reactivation: This process restores the original water-repellent finish. It requires heat and time. I can achieve this by tumble drying the garment at a low temperature for about 30 minutes, if the care label permits. A damp towel can help if the dryer shuts off early. If water beads off the fabric, reactivation was successful. I might also iron the dry garment at a low temperature without steam, placing a towel between the iron and the garment.

- Impregnation: This renews the water- and dirt-repellent layer. It diminishes over time due to wear. Re-impregnation is needed when water no longer beads off after washing and drying. I can use special wash-in agents in the washing machine on a gentle cycle. Alternatively, I apply an impregnation spray to the garment or use special agents during hand washing.

- General Care: I always wash workwear without fabric softener before impregnating. I follow the care label instructions for both the textile and the impregnation agent.

I observe the evolution of water-repellent technology. It now balances high performance with environmental responsibility. Ongoing innovation consistently delivers effective, safer solutions for workers. Understanding these finishes helps me choose and maintain optimal workwear, ensuring longevity and comfort.

FAQ

What is DWR?

I define DWR as Durable Water Repellent. It is a special coating. This coating makes fabrics water-resistant.

Why are PFCs a concern?

I know PFCs are a concern. They build up in the environment. They also link to health issues.

How do I reactivate DWR?

I reactivate DWR with heat. I use a tumble dryer on low heat. I can also use an iron.

Post time: Oct-21-2025